Player protests in professional football this year put a focus on the ongoing fight for social justice in America, but this is not the first time that the football gridiron has been the disputed turf of equal rights. The phrase “Friday night lights” for most Texans conjures up images of teenage players, cheerleaders and marching bands. But it has not always been synonymous with Texas high school football. For much of the twentieth century, only white schools played on Fridays. Black players took the field earlier in the week. The Texas high school football stadium was among the final segregated structures in the state’s public schools. That ended 50 years ago this fall.

The 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision from the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed school segregation, but the decision had broader ramifications that backed the University Interscholastic League firmly into a corner. The UIL, from its inception in 1910 had restricted its membership to “any public white school,” but the El Paso school board sought to integrate immediately in 1955 and questioned the UIL on whether or not that would nullify their schools’ memberships.

The UIL quietly responded several months later: “Be it resolved that the State Executive Committee of the Interscholastic League interpret the language ‘public white school’ as not excluding any public school in Texas which has previously limited its enrollment to white students but which has modified its rules so as to admit students of the Negro race.” In short, any school that integrated could remain a UIL member. That did not sit well with schools that remained all-white, some of which refused to compete against teams that included black players.

However, the UIL did not address its edict that excluded membership by all-black schools that had been competing in the Prairie View Interscholastic League, PVIL. This allowed football segregation to continue standing until the 1967 fall semester–50 years ago–when black athletes were fully integrated into previously all-white programs and all-black schools made their UIL debut. In light of this milestone, my personal commemoration came with a great sense of nostalgia and sadness for a bygone era that produced some of the best high school football in the country, and not under Friday night lights, but on Wednesday and Thursday evenings across the state under the PVIL banner.

Founded in 1920 at a meeting of the Colored Teachers State Association of Texas at what is now Prairie View A&M University, the PVIL mission was to mirror for black kids what the UIL was doing for whites–governing high school athletic, academic, and music competitions. From that meeting, the Texas Interscholastic League of Colored Schools emerged, but not taking its more widely referenced name until the 1960s.

The progress of integration put the PVIL out of business, never mind the talk of a merger with the UIL, which was more a hostile takeover. There was no mass movement of white students to black schools and the UIL didn’t recognize until 2006 what few records were available for PVIL competitions. At its peak, the PVIL included 500 schools, the great majority of which began closing in 1967. Smaller PVIL schools kept the league going for another three seasons, but when the 1970 spring semester ended so, finally, did the PVIL with only eight member schools total continuing to exist in the Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth areas.

“When integration came I felt that they threw us a curve,” said Coach Joe Washington, Sr., who watched the transition in Port Arthur where he lead the Lincoln HS Bumblebees in a program that would include his son and future Oklahoma Sooners’ Heisman candidate, running back Joe Washington, Jr. “The way I took integration, they said ‘we’re going to fix you, we’re going to do away with your schools and bring your kids over to us.’ They put those kids in situations that were new to them and some of them were not able to handle it. Yes, we were probably better off educationally, but not as a race. We lost too many people in the shuffle. Coaches and teachers lost jobs, kids dropped out of school.”

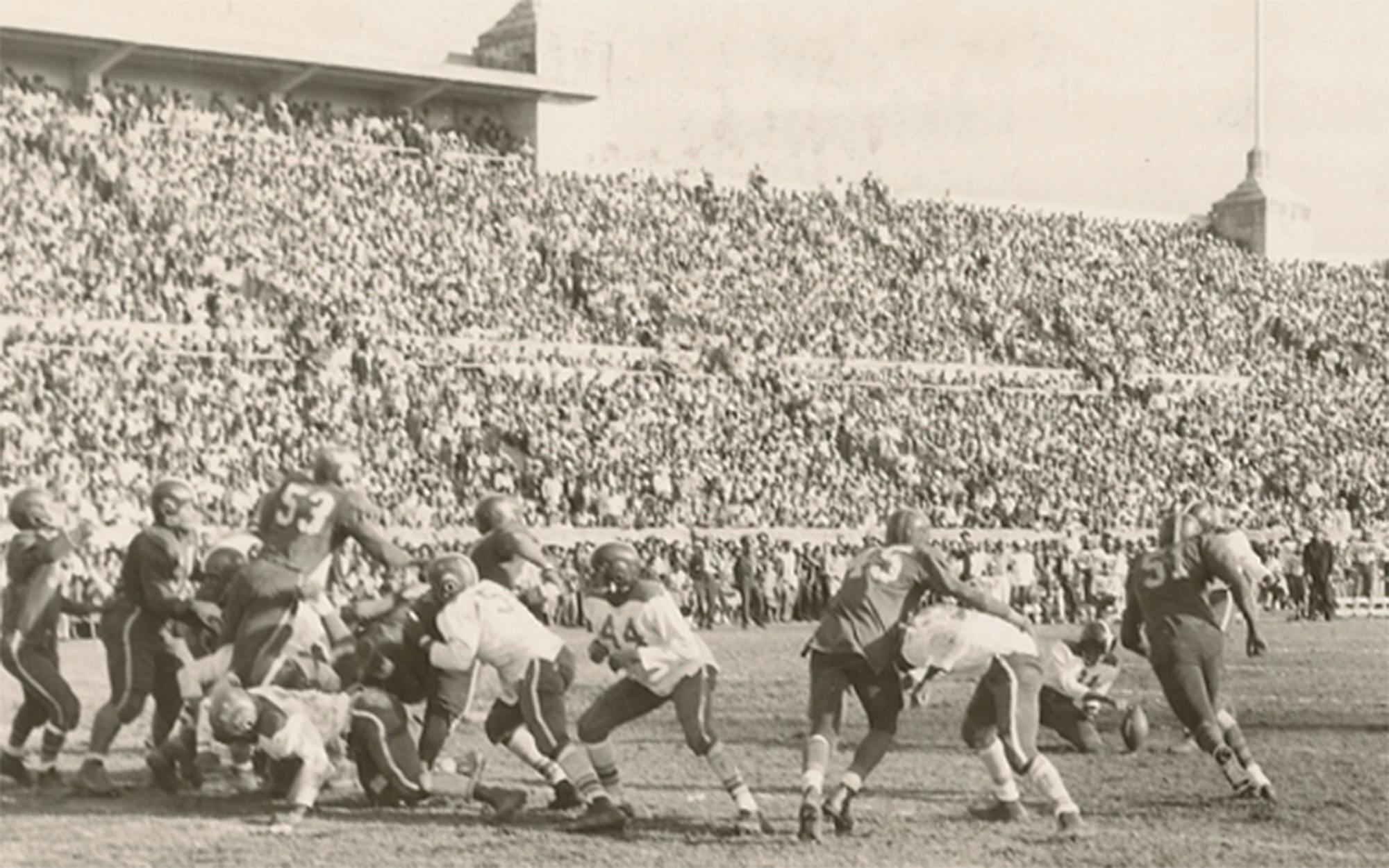

Yet, in its wake, the PVIL left an unheralded legacy of football greatness. Left to their own devices, the black schools created passionate rivalries – in Houston, the annual Thanksgiving Day game between Wheatley and Yates was the most popular high school football game in the nation from the 1940s to 1960s drawing standing room only crowds up to 40,000 fans at Jeppesen Stadium; was led by innovative coaches such as Yates’s Pat Patterson, who won state championships in football, baseball, and basketball; and produced a who’s who of outstanding players with six PVIL alums in the Pro Football Hall of Fame and several others in the College Football Hall of Fame, including Temple Dunbar’s “Mean” Joe Greene, Austin Anderson’s Dick “Night Train” Lane, and Lufkin Dunbar’s Ken Houston.

Also:

- Jerry LeVias, Beaumont Hebert’s sensational running back, was recruited by Hayden Fry at Southern Methodist University in 1965 as the first scholarship player in the old Southwest Conference.

- Beaumont Charlton-Pollard lineman Charles “Bubba” Smith, was an All-American at Michigan State and the first overall pick, by the Baltimore Colts, in the 1967 National Football League draft.

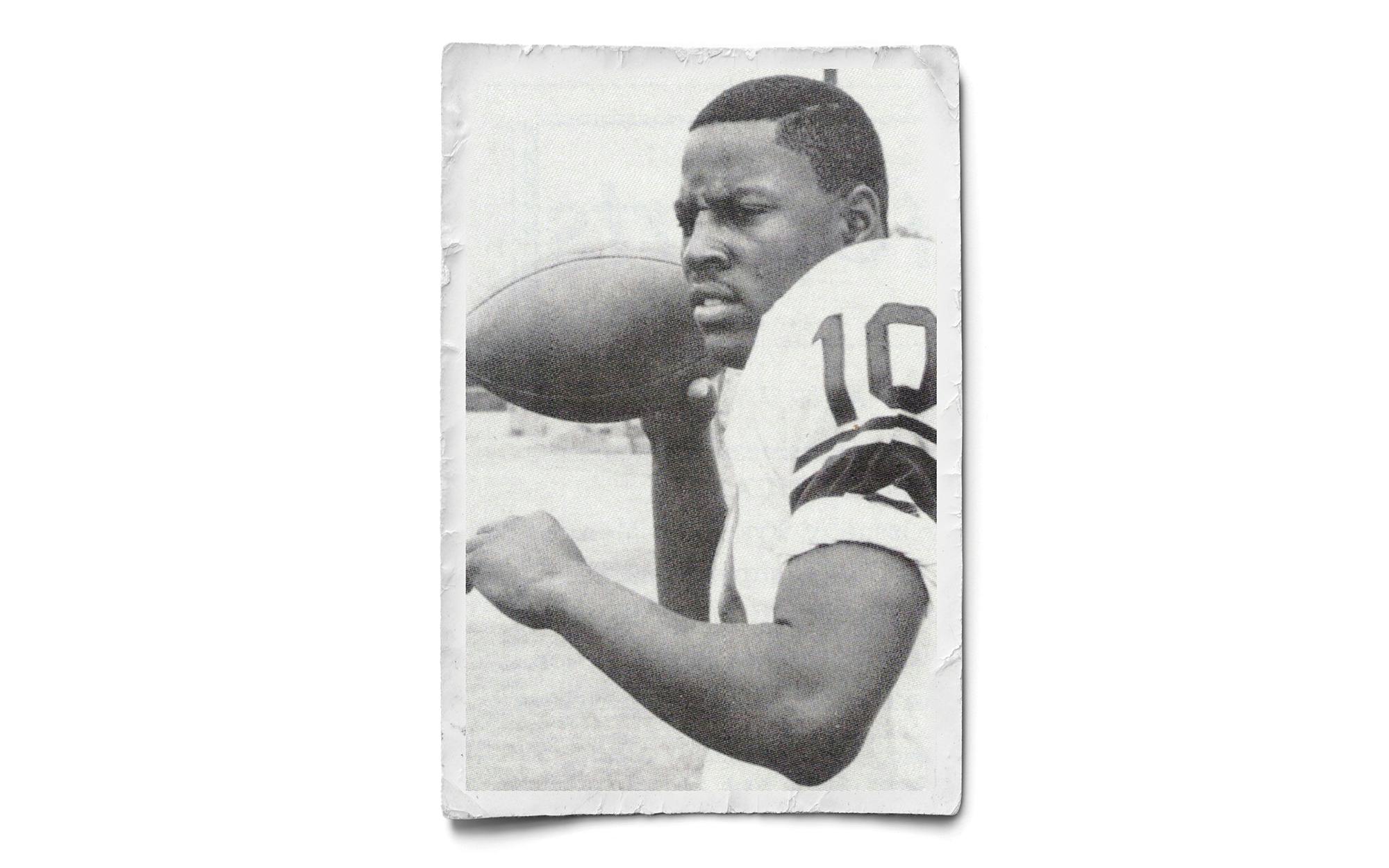

- Houston Washington quarterback Eldridge Dickey, nicknamed “The Lord’s Prayer,” led Tennessee State to two black college national championships and was the first-ever black quarterback taken in the first round of an NFL Draft – 1968 by the Oakland Raiders, who chose Dickey ahead of Alabama’s Ken “Snake” Stabler, the team’s second round pick.

“Our league was special, but the perception was that the UIL was better,” recalled Houston Worthing’s Cliff Branch, a world-class sprinter and three-time Super Bowl champion receiver for the Raiders. “We had a league of our own. I don’t think, back then, we realized what a special league we had, but we did. We didn’t need integration. It was special football and I’m glad I was part of it.”

Given the times, pre-integration, the league was never embraced by media outlets, save for a paragraph here and there, or a game score on the agate page listings, perhaps more mention during the playoffs. But, with the UIL playoff season beginning this week, I can’t help but look at the brackets and subconsciously search for dynastic PVIL teams like the Austin Anderson Yellow Jackets, the Lufkin Dunbar Tigers, or the Conroe Washington Bulldogs, who dominated the PVIL’s 2-A level from 1960 to 1965, winning state titles in 1960 and 1965 with 13-0 records in both seasons and playing in the state championship game in three other seasons.

Lufkin, with quarterback D.C. Nobles, was the first former PVIL team to play for a UIL state title, losing to Daingerfield, 7-6, in the 1968 2-A game. Beaumont Hebert, with fiery UT-bound defensive back Vance Bedford leading the way, would be the first former PVIL team to win a UIL championship (3-A) with its 35-7 win over Gainesville in 1976. However, another former PVIL member, the 1985 Yates team, is considered one of the best – arguably THE best – in UIL history. The 5-A Lions closed their 16-0 season with a 37-0 drubbing of Odessa Permian, ironically, the program noted for Friday Night Lights portrayed in the book, movie and television show.

The high school football that I grew up with was the PVIL brand of collective wide open offenses, hard-hitting defenses and an abundance of speed, as one former player recalled, “everybody could run!” As a PVIL product–Worthing, Class of 1967–I remember the awkwardness of integration, but also the excitement, pride, and togetherness that the league’s games had brought to generations of black communities during an era of social divisiveness and struggle.

I remember the history, and quietly, I celebrate the PVIL.

Michael Hurd is a Houston native and the author of Thursday Night Lights, the Story of Black High School Football in Texas, which was recently released by University of Texas Press. He is a former sportswriter for USA Today, the Austin American-Statesman, The Houston Post, and Yahoo Sports. Currently, he is director for Prairie View A&M University’s Texas Institute for the Preservation of History and Culture. Opinions expressed by Texas Monthly guest columnists are their own.